Thematics aside, The Place beyond the Pines is certainly interesting for its first act. And this interest derives mostly from the fact that Ryan Gosling's character was an unpredictable and erratic figure who never did what I expected him to do. Violent, scary, and very stupid, he was also devoted to his child in an immediate (also slightly terrifying) way. Gosling rides his motorcycle and broods and smokes cigarettes and says very little. His work is not without interest, here, but I think personally I'm a little Goslinged out. Okay not really. But I am a little tired of these brooding, silent figures who have secret love or secret pain or secret shame or something but aren't talking about it. And I know he works with directors other than Derek Cianfrance and Nicolas Winding Refn, but right now those gentlemen's characters seem like the only thing Gosling can do. I know that isn't true, but I also don't think I need any more strong, silent, good-at-revving-engines performances for a while.

Overall, Pines is more a piece about mood than anything else. It is also easy to say "thematics aside" above, but in truth The Place beyond the Pines is all about thematics. It is a kind of long-form meditation on what makes a father, what debt a son has to a father, and how we are or become the fathers to all sorts of sons – even the ones we didn't know we ought to be protecting.

To my mind Pines didn't have much else going for it. It's overly long, and the third act (which ought to be the most exciting section of the film) ends up being the flattest, with characters about whom we care much less than those who have been onscreen for the first two acts. I've read folks complaining on the internet that the third act dragged. To the contrary: the third act is probably the film's most exciting section; it is simply that there's no one onscreen whom we actually like.

Special note about the incredible character-actor Ben Mendelsohn, who is really superb in a supporting role as Gosling's only friend.

Pines is told mostly from the fathers' point(s) of view. Even in the third act when we adopt the son's viewpoint, we are watching as though we were his parent, so the point of view of the father predominates throughout Pines. In Jeff Nichols' Mud, we see the viewpoint of the son only.

~

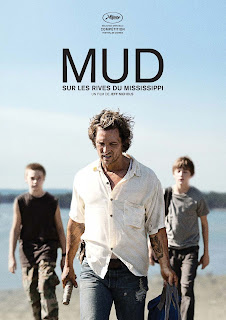

Mud was everything I needed it to be. Two boys discover an outlaw named Mud on an island somewhere in the Mississippi River and decide to help him for no apparent reason other than that he is interesting and tells good stories. (I can relate; I love a good story.)

Ellis and Neckbone (That's a great handle, kid Matthew McConaughey tells him) are teenagers who really don't know what they're doing. We follow Ellis as he tries to get a much older teenage girl to be his girlfriend, deal with his parents' breakup, and assert himself as a full-grown individual. He is scared and naive and lovable, and the actor who plays him (Tye Sheridan) is unbelievably good. Watching this boy enjoy his first kiss will definitely be a cinematic highlight of 2013 for me.

Ellis is looking for another father figure – one different from his own father, I mean – and this outlaw is dangerous and exciting and apparently willing to fight for the woman he loves. Ellis admires that. Neckbone, too, needs more of a father in his life. His own guardian is a hilarious uncle played by Michael Shannon, who just wants his nephew to hang out with him. Of course, our father figures need their own fathers, too, and still need help even when they're grown. Mud is an orphan, too.

Ellis is looking for another father figure – one different from his own father, I mean – and this outlaw is dangerous and exciting and apparently willing to fight for the woman he loves. Ellis admires that. Neckbone, too, needs more of a father in his life. His own guardian is a hilarious uncle played by Michael Shannon, who just wants his nephew to hang out with him. Of course, our father figures need their own fathers, too, and still need help even when they're grown. Mud is an orphan, too.Mud is a suspense film, though, not a meditation. And, like he does in Take Shelter, Nichols handles the suspense superbly. Mud builds and builds until I absolutely loved the characters in the film and didn't think I'd be able to bear it if harm came to any of them. And it is a tribute to Nichols' excellent filmmaking that in a film that isn't a meditation – in a film that is really just a good old-fashioned genre picture – I spent most of my time thinking about fatherhood, about what we want our fathers to be, about what we need from them, and of the fantasies we project onto them about their abilities.

Perhaps it isn't fair to compare Mud to The Place beyond the Pines – they are, after all, working on totally different things – but I saw them back to back and they are both so much about fatherhood that I will probably always think about them together.