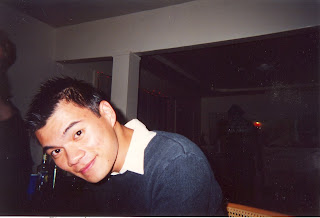

I am finding writing about my friend Andrew very difficult to do. Andrew (who had just turned twenty-eight) was an

actor in Los Angeles. We went to college together from 2000 to 2003.

Andrew was my yoga partner. He was the third in the Ayana/Andrew/Aaron triangle. He was my drinking buddy. He was the Guildenstern to my Rosencrantz (literally—in the second production of

Hamlet we did together—but offstage, too).

Funny about Andrew: he was always competing. With me, with the other actors we went to school with, with his directors, with his teachers, with other actors we worked with, with David Suchet and Ian Richardson, with himself. I admired this about him even as it frustrated the hell out of me. He demanded excellence of everyone, including and especially himself. We used to joke that we could even make a contest out of doing yoga: here we are supposed to be having a spiritual experience and getting in touch with our breath and the two of us would be trying to outdo one another at proud warrior.

We met in 2000 working on a production of Tom Stoppard's

Arcadia directed by Bob Gilbert. He was a freshman in the theatre department and I was toying with the idea of joining the theatre department at Cal Poly Pomona. Andrew played Captain Brice and I played Mr. Noakes—we were freshmen, so we were cast as the supporting players but we felt privileged to be onstage at all. (I will never forget A. Cohen who played Septimus hilariously telling me to go fuck myself in a British dialect and sending me up in the middle of a run.) Andrew told me later that from the moment we met he knew that when we were seniors we would be competing for all the roles at school. He was wrong, but that competitiveness was typical.

I loved acting with Andrew. We would compete at this too, even when we were onstage together. He was superb at taking focus and giving it back if he felt like giving it back. He knew the stage so well that if he felt like taking the stage, he would devise a cross or a small gesture and just take it. In 2003, we were working on a production of

Hamlet. The actor playing Horatio got another gig and they moved Andrew from playing Guildenstern into the Horatio role. As he went through his old Guildenstern blocking for the new Guildenstern, he told the new guy: "and this moment is when I try to take stage from Aaron." I scoffed. And told him I

let him take stage. We just grinned at one another.

I loved directing him, too. Back in college—it must have been our senior year—Andrew had gotten himself suspended from department shows. I forget now what he had done. I didn't think much of it then: none of us did. Marcos, Allan, Carlos, Justin and I devised a production of Moisés Kaufman's

Gross Indecency: the Three Trials of Oscar Wilde for Andrew to star in. Andrew played Wilde. (Carlos was particularly brilliant in the show, too.) The last time I talked to Andrew he brought up the show. "You told me to act like Christ," he reminded me. "

And you will never let me forget it," I told him. "It's alright, actually," he said. "I knew what you meant."

I think he was misremembering. It was really awful direction. I still use it as an example of things a director shouldn't say.

Actually, it's odd of him to misremember: Andrew never forgot anything. It used to drive me crazy. I would make some offhanded comment and six months later he would bring it up. "I love Al Pacino," I would say. "Really?" he would say, and his tone would level because he sensed victory. "You said you thought he was a ham." "I did?" I would ask, knowing that I probably had said exactly that, but not remembering it at all. Leave it to Andrew to remember every rude thing I ever said about anyone. Not that his memory wasn't occasionally useful. This one time at 6:00 in the morning in the Studio at Cal Poly, the VCR wouldn't work for a yoga session with Andrew, Jen Carr and me, and Andrew recited the entire Bryan Kest routine from memory.

Rosencrantz and Guildenstern offstage, too: This used to happen to both of us all the time. Someone would be talking about him to me and call him Aaron or someone would refer to me as Andrew. The names are similar, after all. This annoyed both of us occasionally and amused us at other times. It still happens. I was talking to my friend Linda about Andrew just yesterday and she did both: she called me Andrew and then five or ten minutes later she called him Aaron. He and I influenced each other so much that I always thought—even when it was annoying—that the mistake always made a sort of sense.

Andrew and I could exchange a look across a room of people and we would know what each other was thinking. I loved that.

Andrew was obsessed with Shakespeare. Totally, completely obsessed. He would become enamored with British Shakespearean actors: Roger Rees and Simon Russell Beale and Antony Sher. (He did this fantastic impression of Patrick Magee from

A Clockwork Orange: "More wine?" It was hilarious.) He rented DVDs of old productions of the Bard's plays done for the BBC and at the National. He would read up on different ways that actors approached parts—and knew all of this trivia. So and so played Caliban as a dog; this actor played him as a fish; this actor—I have forgotten all their names—played him as though there was nothing abnormal about him at all (the way, of course, that Andrew played the part when

he finally did

The Tempest.) He would memorize lengthy speeches, working for hours by himself on nuances in a monologue from

Richard II (he was always partial to

RII). He brought it up the last time we spoke:

"I wasted time and now doth time waste me"

He told me he learned the speech in college but nowadays he felt like he knew what it meant.

Andrew would probably scoff at me if he read this: tell me I was getting sentimental in my old age.

Andrew was my best friend for a long time, and we remained close, as far apart geographically as we were. He would still call me whenever he saw a piece of theatre that really inspired him. I loved him very, very much. I told him this all the time, so I have no fears or regrets about him not knowing.

Andrew and I used to talk all the time about what we called "the place of creation." I had forgotten about this, but he (typically) reminded me about it recently. The place of creation was a space of beginning, a space in the body. The place of creation, though, is not a

location so much as it is an

activity. As actors we would try to get to this place: by stripping away the tensions, lies, preoccupations, memories that held us back. We would try to be free of memory, free of falsehoods, free of pretensions. Our goal was the place of creation: from which, allegedly, real art was supposed to spring. I am skeptical now—cynical, stuffy academic that I am—but Andrew hadn't given up on the place of creation.

I was recently writing about a few of the Dadas—the bold, uncompromising ones who disappeared or committed suicide—Jacques Rigaut and Arthur Cravan and Julien Torma. Their suicides were political and artistic statements. They refused to take part in what they saw as the fraud of Western History and Culture; they refused to live in a society that allowed and condoned World War I. They also wanted to create art, but only art that would disappear as soon as it was created. Some burned their own work as soon as it was written.

The Dadas who disappeared fascinate me the most. They wanted to kill themselves—they saw it as the only ethical act—but they disappeared from society instead, vanishing and leaving only traces, which those remaining mostly unsuccessfully would attempt to piece together. It occurred to me that those Dadas who disappeared managed the perfect act: to kill oneself without dying. This is, perhaps, another way of phrasing our "place of creation": an artistic stripping, a killing of the self, that does not cause death, but is, instead, generative.

Andrew's own memories will not haunt him any more. He killed the past, stripped memory of its power, unfastened desire's chokehold on his life and work. The traces, fragments, and memories above are some of what remains. But I also believe that killing memory and wresting free of desire can be generative, creative. I am heartbroken that I have lost my friend, but I also believed in him, trusted him, loved him. And though he himself is free of memory, I know I will never forget him.

Pete Docter's

Pete Docter's  Henry Selick's

Henry Selick's